Traditional uses and cultural importance

| |

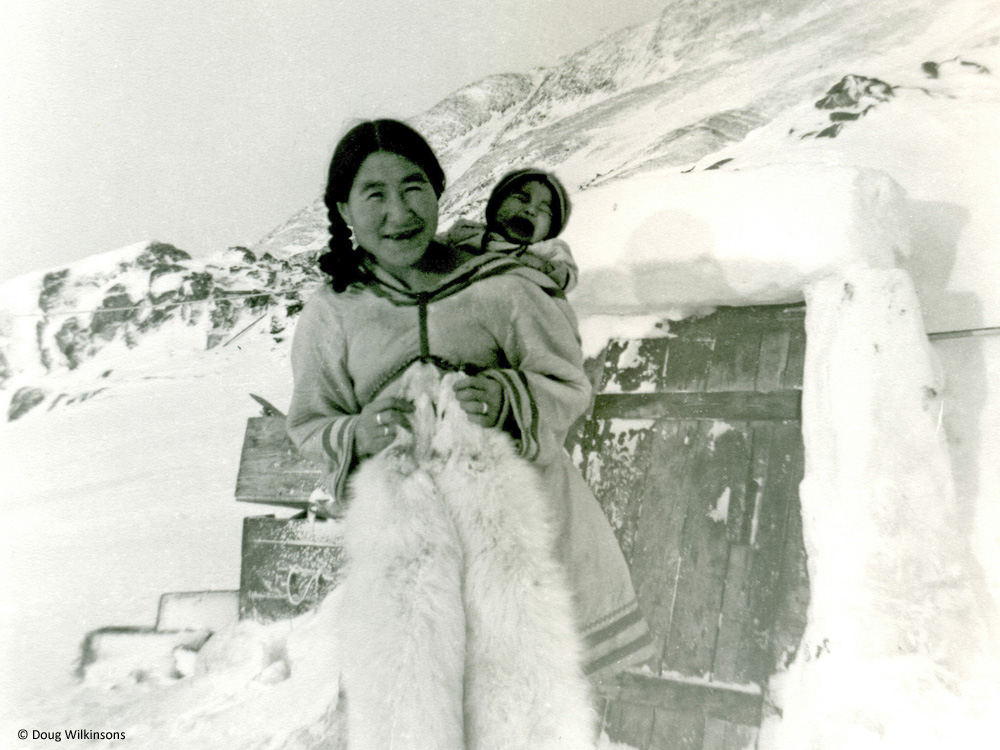

| Qillaq Idlout holding two fox furs (1953) |

The trade of arctic fox furs has been the main source of income for Inuit families from the 1920s to the 1970s. During that period, the pelts of arctic foxes were sold to the Hudson Bay Company trading post, established in Pond Inlet in 1921, in exchange of essential goods such as riffles, ammunitions, sowing material, soap, etc. According to the elders and hunters interviewed, arctic foxes were very important during that period as they were almost the only way to obtain goods that would facilitate daily life on the land.

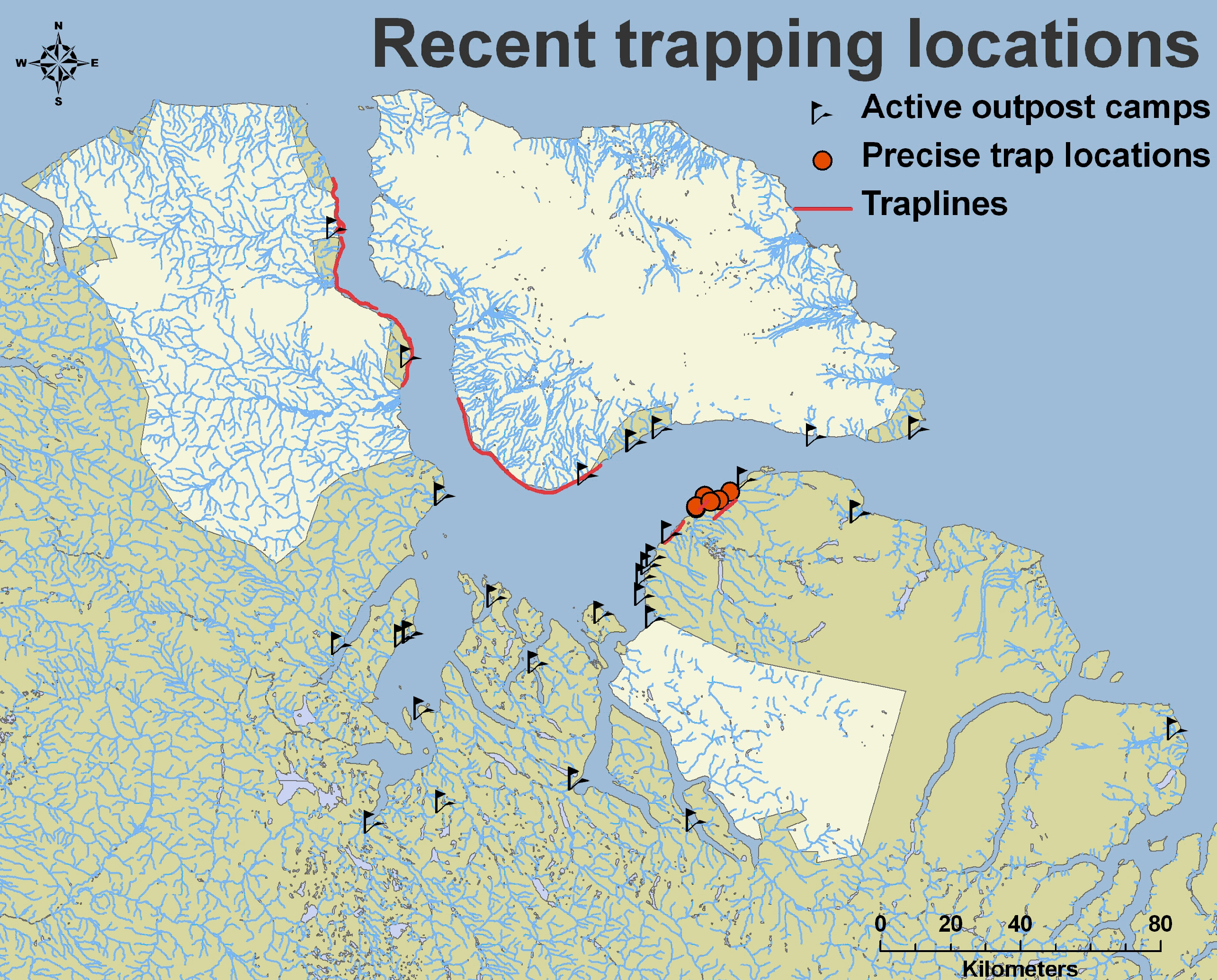

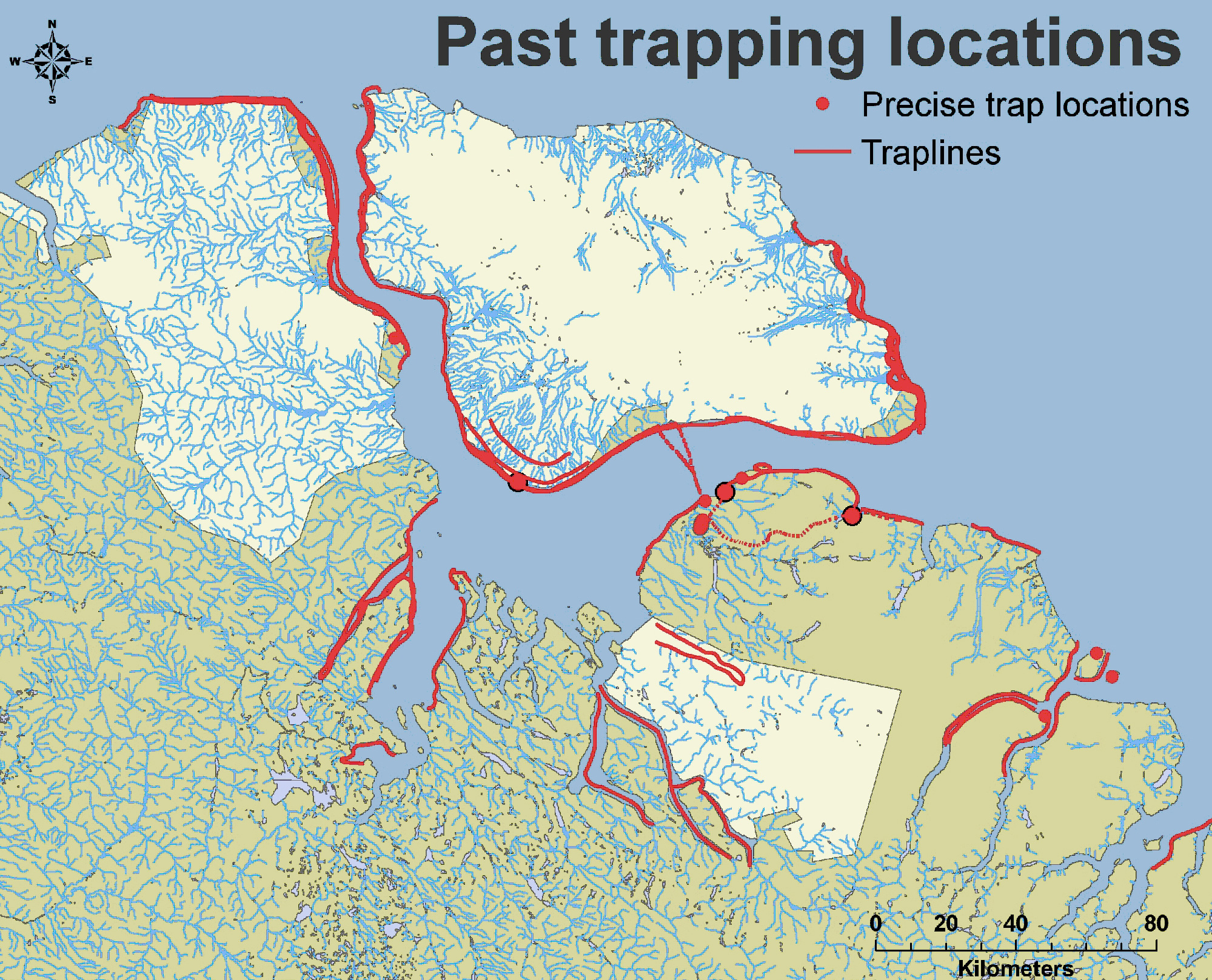

To obtain fox furs to be traded, interviewees mentioned that almost every Inuit families dedicated their winters to fox trapping. Trap lines were mostly located along the coastline. This facilitated travel by dog teams and allowed them to hunt for seals which Inuit families depended on for food but also for light and warmth (through seal oil lamp).

Besides being used for trading, fox furs were sometimes used for clothing. The tail could be made into scarves, and the tail tendons used as thread for sowing. Fox furs could also be used for hood trims or placed around the waist area to keep warm. This was called ‘Qaumailissaq’ in Inuktitut.

Fox furs could also be used by hunters when going seal hunting. Placed under the feet, the fur would allow them to approach seal holes without being heard, thus facilitating the hunt. Hare fur was also used for that purpose. After the settlement of Inuit families in the late 1960s, fur trading remained an important economic activity, until the collapse of the fur trade market in the 1980s. Today, fox furs are used mainly for hood trims. To some elders and hunters however, fox trapping remains an important activity as it is one way to keep the Inuit traditions alive.

Ecology of the arctic fox

Winter feeding ecology and distribution

According to scientific information, not much is known about the winter diet of arctic foxes from the area of Pond Inlet. Elders and hunters from the area were therefore asked to share their knowledge about the feeding habits of arctic foxes and the location where they are mostly seen during the winter. Of the 21 elders and hunters interviewed 18 were able to comment on the location where arctic foxes are most often seen during that season. Of these, eight commented that they observed arctic foxes mostly on the land, while three mentioned seeing them mostly on the shorelines, three others either on the land or the ice, two on the sea ice, one at the floe edge (where the sea ice meets the open sea), and one at the floe edge and on the mainland.

Sixteen informants commented on the winter diet of the arctic fox. According to them, its diet consists of various items: the most often cited being carcasses of sea mammal and lemmings. Some specified that these carcasses came from beached animals or were left on the ice by polar bears or hunters. Caribou meat, arctic hares, birds (most likely ptarmigans), and food caches prepared by hunters were also cited as items consumed by foxes in winter.

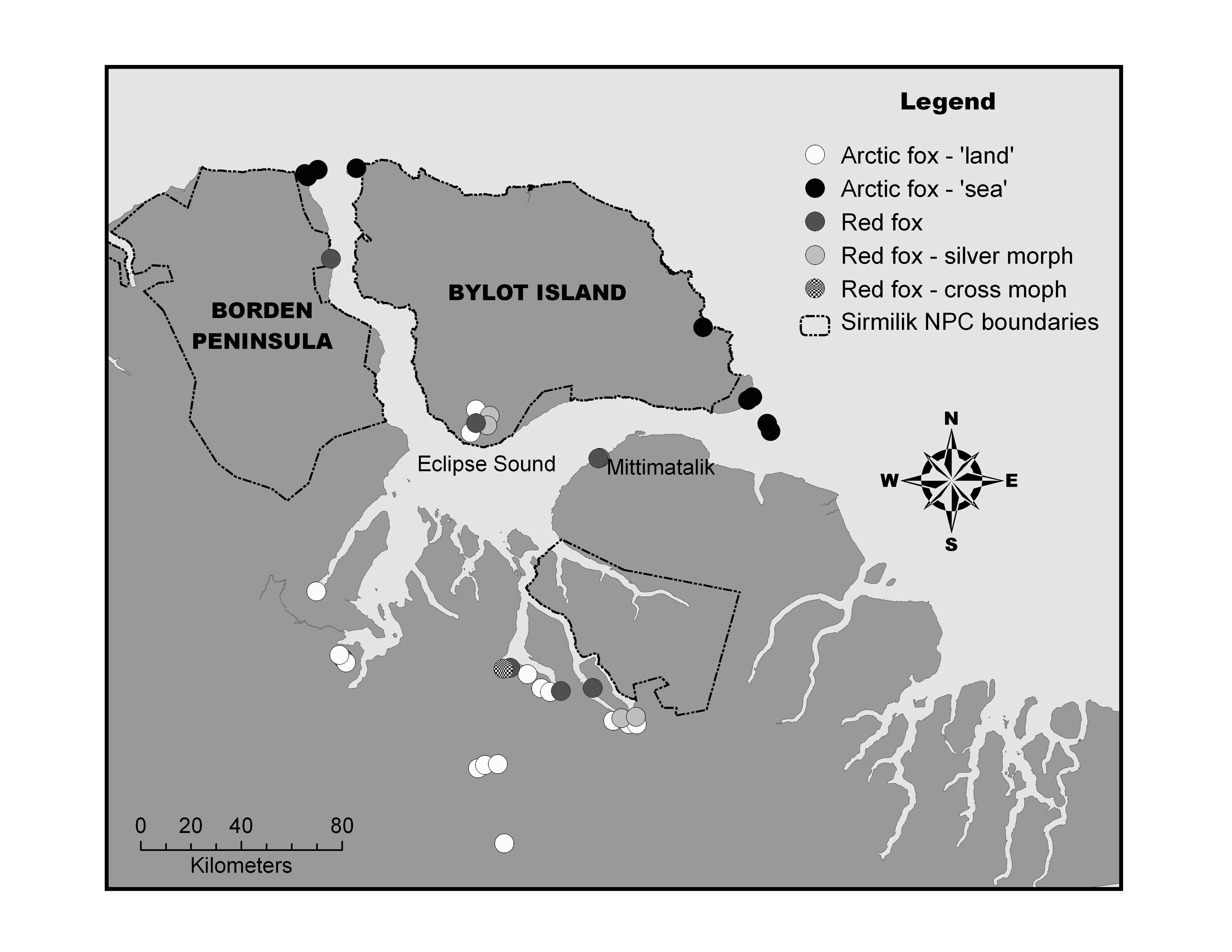

Interestingly, eleven informants unexpectedly reported on the existence of two types of arctic foxes that can be distinguished by their different wintering strategies: one type mostly remaining on the land during the cold season and the other remaining on the sea ice. According to these elders and hunters the two types of foxes can be distinguished by the facts that the "land fox" has a thicker fur, a whiter fur and a larger body size. Other informants also mentioned that "land foxes" have a harder and less oily fat, longer fur, thinner skin, are better to eat and turn white earlier in the winter. Variations in food sources and temperature gradient between the sea ice and the land are the reasons raised by seven persons to explain the differences between the "land" and "sea" foxes.

Interestingly most informants spontaneously reported that arctic foxes engage in a massive migration from March to April during which foxes move towards the sea ice to feed on newborn ringed seal pups.

Arrival of the red fox in the area

Red foxes have only recently expanded their range to the Baffin Island area. This recent colonization has only been sparsely documented and the impact it may have on arctic fox populations raises some concerns. In order to complement the information available on the arrival of the red fox in the area of Pond Inlet, based on pelt records from the Hudson Bay Company trading post, interviewees were asked if they remembered having seen a red fox for the first time in their hunting area. Seventeen informants provided comments, of which three mentioned having always seen an occasional red fox, one believed, based on his parents, that red foxes have always been around, and the others remembered their first encounter with a red fox. Among the persons interviewed who remembered their first sighting, one stated having seen one for the first time in 1943, in Igloolik, two stated having seen one in 1947-1948 in the Pond Inlet area, eight informants stated their first sighting in the 1950s and two others in the 1960s. Nine out of ten elders and hunters mentioned that since it arrived around Pond Inlet, the red fox has increased in numbers. Moreover, the silver and cross color morphs (variation) of the red fox have been sighted in the area.

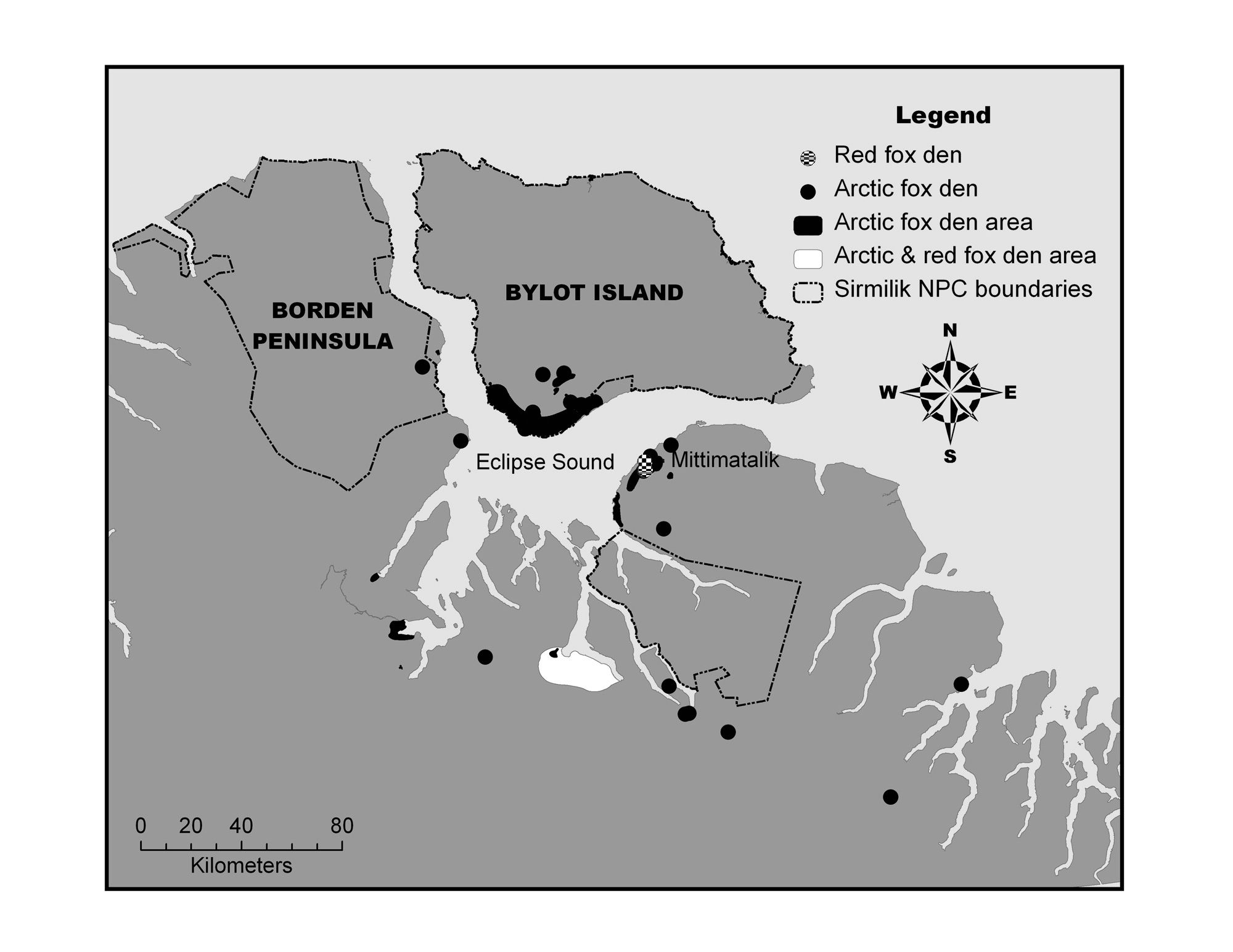

Locations and characteristics of denning areas

People interviewed were asked to comment on the best area for foxes to build a den. Observed denning locations were noted on maps, which included pinpointed locations as well as general areas for both arctic and red fox dens. Seventeen informants also commented on the characteristics defining good denning habitats. The majority mentioned the presence of a sandy soil or sandy area as an important characteristic. The presence of fish, places with abundant soil, low lying areas and small hills were also cited as important characteristics.

| Elder-youth camp | Inuit knowledge on geese |